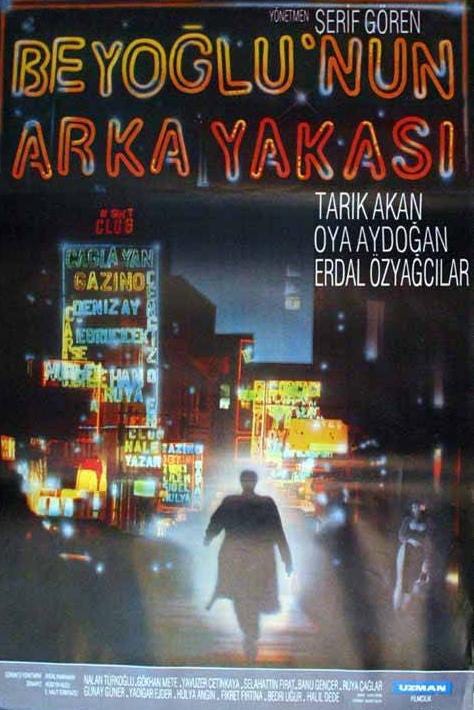

All Eyes on Istanbul Film Series #3: Beyoğlu'nun Arka Yakası

This compelling 1986 film stars the legendary Tarık Akan as a civil servant who suddenly finds himself in the middle of a debaucherous, precarious night in a seedy, crime-ridden Beyoğlu.

Currently available on MUBI, Beyoğlu’nun Arka Yakası (The Other Side of Beyoğlu) has been the subject of a few interesting conversations in Turkish on Twitter recently, and I had been planning on writing about the film for this series and was thrilled to watch it again. It was directed by Şerif Gören, who passed away late last year and was most famously known for completing the Yılmaz Güney film Yol, among the most striking and iconic in the history of Turkish cinema.

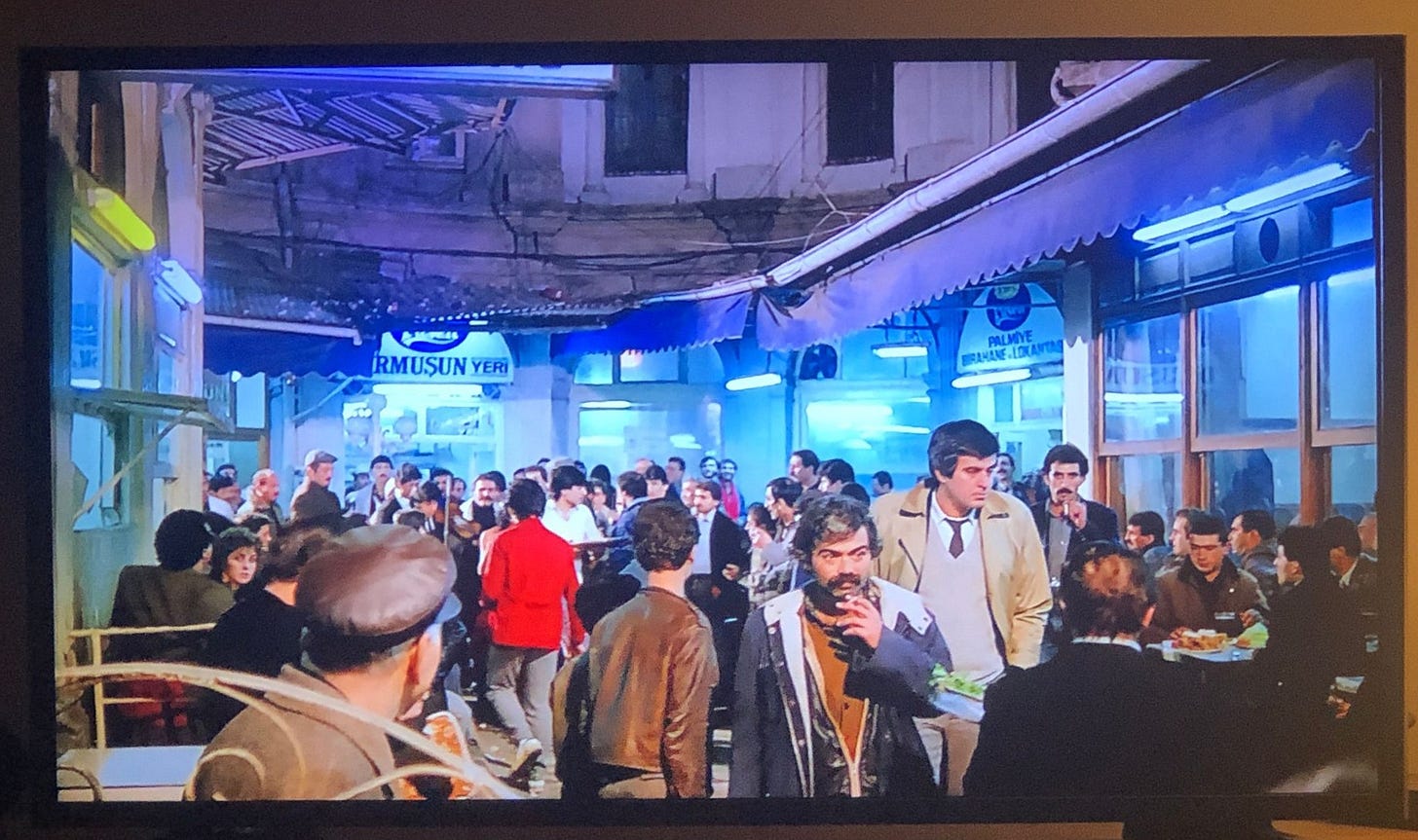

Gören’s 1986 film stars Tarık Akan, one of the most acclaimed and beloved Turkish actors of all time. When Akan passed away in 2016, there were still lots of shops in Istanbul selling bootleg DVDs. One such kiosk in Kurtuluş featured an array of his films in a tribute of sorts, and this is where I bought my copy of Beyoğlu’nun Arka Yakası, which I’ve watched several times and is one of my favorite Turkish films. Akan plays Haydar, a civil servant who gets into an argument with his wife and proceeds to storm out of the house and blow off steam in the streets of Beyoğlu. His initial plan was to grab a couple beers and a sandwich, but the night takes an insidious turn. The Beyoğlu of the time is rough around the edges to say the least, and a man runs through a crowd with a bloody knife as Haydar is sipping his beer. A few heads turn, but most of the onlookers carry on with their evening as if this is a routine sight.

Amid a massive group of men, the only woman in sight is a belly dancer. Haydar has just received his monthly salary, and for some reason has all of it in his wallet. A street kid notices this, and gets Haydar to buy him a beer. The boy steers him in the direction of Çarli, a charismatic pimp and taxi driver played by Erdal Özyağcılar. Çarli knows the streets well and before long has Haydar in a nightclub seated next to Zümrüt, a charming, voluptuous prostitute played by Oya Erdoğan. (Note: while director Gören, Erdoğan and Akan have all passed away, Özyağcılar is still alive and regularly acting). They are served glass of whisky after whisky, and Zümrüt holds her liquor considerably better than Haydar does.

They go back to a hotel where Haydar hopes to get lucky, but Zümrüt has other plans. She orders a bottle of rakı (drinking rakı before or after several whiskys is not a good idea, believe me) and pours Haydar a glass while she sips water. When he passes out, she steals most of his salary from his wallet, leaving behind a few notes out of mercy before absconding. Eventually Haydar wakes up and storms out of the hotel screaming to no one in particular that he has been relieved of his salary.

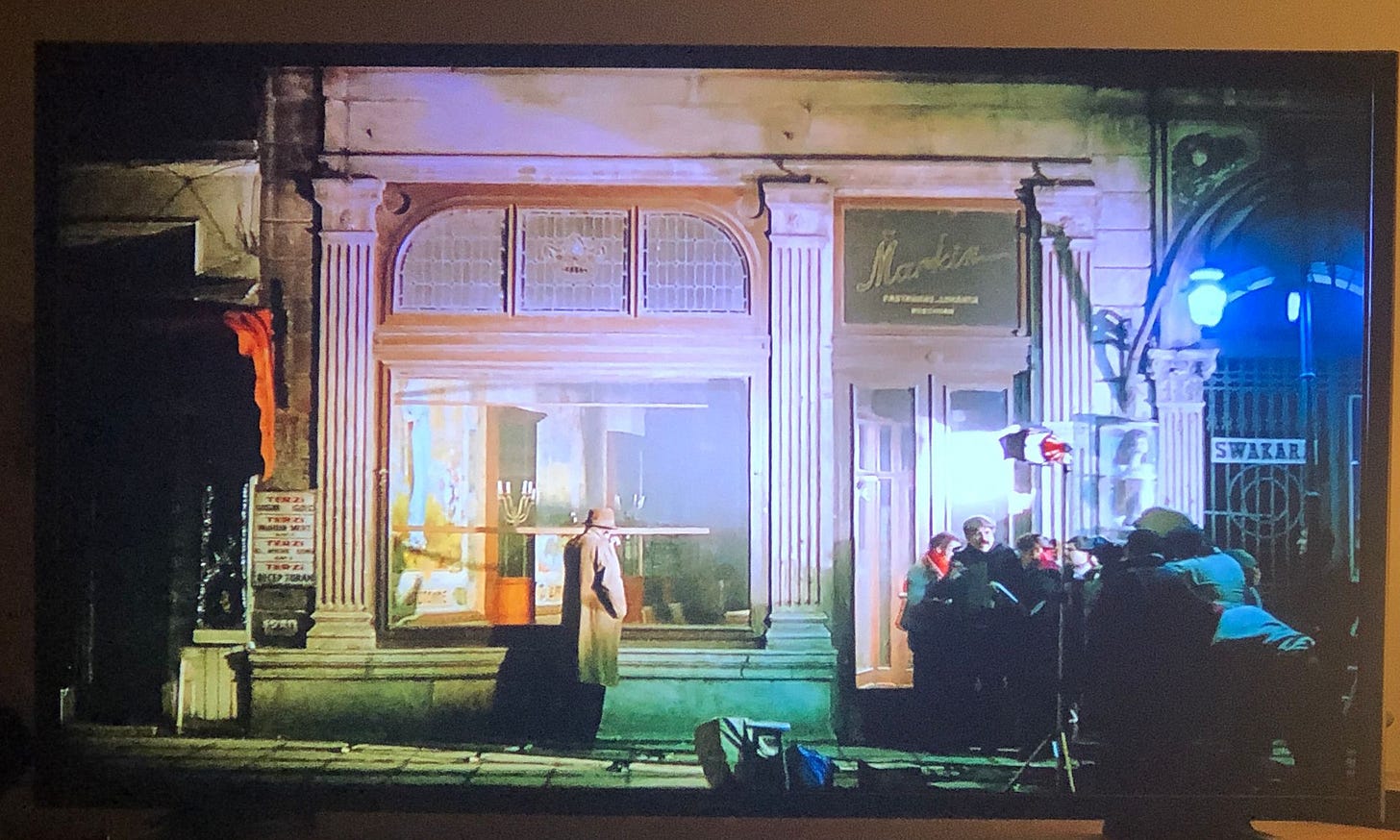

There is a subplot involving a film crew shooting a documentary highlighting some of Beyoğlu’s historic landmarks, the Galata Tower, The Church of Saint Anthony of Padua, and Markiz Patiserrie (the latter of which was opened in 1940 and famous for its exquisite Art Nouveau ceramic paneling. It has been closed for years, but the interior has been preserved and it is supposedly slated to reopen soon).

In the middle of Haydar’s wild night, he encounters the film crew in numerous locations (it is followed everywhere by a curious, large group of men) and he keeps trying to get closer to the set, only to be rebuffed each time. Haydar also encounters an old friend whom with he did his mandatory military service with. The man sells watches on the streets of Beyoğlu and snorts downer drugs as the night comes to an end.

Will Haydar find Zümrüt and Çarli and manage to get his salary back? Will he be in even more trouble with his wife than he already was when she booted him out of the house? You’ll have to find out, as no more plot details will be provided here. The most fascinating aspect of this film is the visual setting of Beyoğlu’s backstreets at night in 1986. It practically glitters with depravity, there is excitement and and chaos lurking around every corner. The sparkling signs of the countless nightclubs and bars are both intriguing and menacing. İstiklal Avenue had yet to be pedestrianized, and the social and physical fabric of Beyoğlu was starkly different. Very few non-working women are seen in the film, because that was the reality of the area at the time. For the most part, young couples or groups of friends went elsewhere to socialize, men went to Beyoğlu for illicit fun.

After the demolitions in Tarlabaşı and the pedestrianization of İstiklal Avenue in 1990, Beyoğlu rapidly transformed and eventually became the coveted center of Istanbul nightlife, with venues catering to people from all walks of life, most notably the city’s LGBTQ community and the underground music scene. The area continues to undergo changes as the hyper-commercialization of Istiklal over the past 10-15 years has resulted in numerous malls and dozens of chain stores, while many clubs and bars that were open for years were forced to close their doors. However, the culture of the area has not been sterilized entirely, and there continue to be storied establishments that insist on remaining open in Beyoğlu, while many new excellent bars and restaurants have opened in recent years. Beyoğlu’nun Arka Yakası is a fascinating window into what the district was like forty years ago, employing an often-comedic approach while not sugarcoating the reality of the crime, drugs, violence and intimidating, male-dominated atmosphere that Beyoğlu was known for at the time.

The movies you choose and your analysis are par-excellence, bringing up a lot of nostalgia.

really wonderful review, Paul – always fascinating to have this kind of comparison of times past and present.